PrairieFire Rural Action – NCCC

(Iowa Family Farm organization) – (National Council of Churches of Christ)

ECUMENICAL AND INTERFAITH STATEMENTS and POLICY STATEMENTS OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF THE CHURCHES OF CHRIST IN THE U.S.A.

In recent years, ecumenical bodies at the state and national level have taken an increasingly active and public role on rural crisis issues and state and federal farm policy.

The first document in this Section is “A Resolution by Religious and Ecumenical leaders of the United States,” passed by an ecumenical and interfaith gathering of religious leaders in Kansas City, Missouri, in November, 1986. The Resolution stands in clear support of the principles of the Family Farm Act.

Also included here is a “Declaration on Rural Crisis” adopted by the National Interreligious Conference on Rural Life, held in Chicago in February, 1987. This Conference of Christians and Jews marked a major step in the development of strong interfaith policy positions on rural issues and public policy development.

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. (NCC) is comprised of thirty-one communions — Protestant, Orthodox and Anglican church bodies with a combined membership of 40 million Christians. It is the primary national expression of the ecumenical movement in the United States.

This special section includes the NCC’s basic Policy Statement adopted in 1958, “Ethical Goals for Agricultural Policy,” and six related Resolutions passed by the Governing Board since 1983:

1. On the Status of the Family Farm May 12, 1983

2. On the Status of Black-Owned Farm Land in the U.S. November 11, 1983

3. A Call for Justice and Action May 17, 1984

4. On the Exploitation of the Rural Crisis by Extremist Organizations November 8, 1985

5. Save The Family Farm Act of 1986 November 6, 1986

6. Resolution on the “Christian Identity” Movement November 6, 1986

Of special note is the Resolution passed unanimously by the Governing Board on November 62 19861 in support of the Save The Family Farm Act of 1986.

National Council of the Churches of Christ, 475 Riverside Drive, New York, NY 10115

RESOLUTION ON THE STATUS OF THE FAMILY FARM

(Adopted by the Governing Board, May 12, 1983)

In order to restore some integrity to farm tax and credit policies which have increasingly favored high-income: expanding firms at the expense of small and modest sized family farms in the U.S., the Governing Board of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. calls upon the Congress and the Administration to develop and implement policies which:

(1) restore the limited resource loan program of loans to low-equitv and low-income farmers and establish it as the principal loan program of the Farmers Home Administration;

(2) restructure eligibility guidelines for all other Farmers Home Administration farm loan programs so that larger-than-family farms are not eligible for this kind of assistance:

(3) provide proper servicing to borrowers who for no fault of their own are unable to meet scheduled loan payments but who show evidence of ability to pay when agricultural prices stabilize at levels which afford them the opportunity to do so; specifically, loan deferrals should be granted on a case-by-case basis under provisions which guarantee full and fair consideration of each applicant for a deferral and which safeguard the procedural rights of the borrower, including the right or administrative appeal; and

(4) eliminate the use of the investment tax credit for specialized farm buildings for the production of livestock and for the purchase of irrigation equipment which is used to irrigate land which is not considered to be irrigable within soil conservation standards.

The Governing Board further cells upon its member denominations, local congregations, end affiliate organizations to advocate for and support such measures.

Resolution on THE STATUS OF THE FAMILY FARM

Introduction

One of the most complex problems facing the United States government today is the financial crisis in agriculture. Partly the product of farmers’ success in improving productivity and partly the product of farm policies which have failed to stabilize farm income. this crisis threatens to erode the family farm base of American agriculture more than any development in our lifetimes.

Neither recent Congresses nor recent administrations have responded responsibly to this growing crisis. To the contrary, there has been a tendency on the part of public officials to avoid the issue by opening public credit programs to an ever-wider group of larger farms and offering tax concessions which encourage further expansion on the part of these farms. The result is more concentration in production, diminished economic opportunity for farms of modest means. and greater financial vulnerability for our food system as a whole. These trends undermine an owner-operated system of agriculture, which a substantial body of scientific literature has established as the most efficient unit of production.

Particularly grievous has been: (1) the steady deterioration in the services afforded small farmers with limited resources by the Farmers Home Administration and the corresponding shift in that agency’s emphasis to larger-than-family farms: and (2) the expansion of the investment tax credit, a superfluous subsidy to capital which invites unneeded investments by tax-motivated investors in areas of agriculture already sufficiently capitalized. These policies have tended to reward the rich at the expense of the poor, and to diminish economic justice.

The general direction of these and other policies is therefore viewed as contrary to the Ethical Goals for Agricultural Policy adopted by the General Board of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. on June 4. 1958, which called for the development of “… programs which will enlarge the opportunities for low-income farm families to earn adequate incomes and achieve satis- factory levels of living…”

Background Considerations

Credit: Since the 1940’s, the Farmers Home Administration has provided credit as a last resort to farmers who could not get it elsewhere. Its purpose has been to help tenant farmers become owners and to help marginal farmers reach the point where they could operate through normal commercial credit.

In recent years, the government has reduced services to such farmers while expanding Farmers Home Administration credit to larger, more aggressive farmers. In 1978, Congress eliminated the interest subsidy from 80% of Farmers Home Administration’s “regular” loans. reserving the lower interest loans “limited resource” (LR) borrowers, vaguely defined as those who could not afford the regular interest rate. At the same time, Congress established an Economic Emergency (EB) loan program for larger-than-family-sized farmers including those who do not depend on farm income for a living. By 1979, the EEprogram was larger than the regular loan program, and limited-resource borrowers, the group for whom Farmers Home Administration was established, were getting less than 10% of the agency’s farm loans.

The present Administration has opposed re-authorization of the limited resource program and has opposed any appropriation for it. Last year, it spent only half the limited resource allocation, despite authorizing legislation requiring it to make the loans. Meantime, Congress, is considering legislation to strengthen the EE program by making it mandatory.

At the same time, the Administration has generally resisted efforts to take Farmers Home Administration procedures more open and fair for the borrower. This has been particularly true in the case of requests for deferrals, or one-year extensions of overdue loans in cases where the delinquency is for reasons beyond the borrower’s control. A U.S. District Court case (Curry 7. Block) requires the Administration to develop criteria for such deferrals, but Farmers Home Administration has appealed the case to the Circuit Court. Congress is considering legislation requiring implementation of the deferral policy. About 25% of Home Administration borrowers are delinquent, and that proportion is expected to increase.

Tax Policy: The general effect of U.S. income tax policy on the structure of American agriculture has been to encourage non-farm investment, concentration of production, and the separation of ownership from operation. Recent major studies by the United States Department of Agriculture and land-grant universitiesconfirm this.

The effect has been particularly strong in livestock production which h= become more capital-intensive and therefore more susceptible to tax-motivated investment. The University of Missouri reports that about 13% of the slaughter hogs in the U.S; now come from large operations, and in Nebraska, the Center for Rural Affairs has documented that 24% of the feeder-pig crop (an especially important crop for beginning farmers) now comes from corporate hog factories.A high-income investor in such a facility can receive as much as 50% of his her initial investment back in the first year of operation through reduced federal taxes, and over the life of the facility can receive as much as 80%. This subsidy is attracting investment capital into an area of agricultural production which is already sufficiently capitalized. United States Department of Agriculture reports that the U.S. hog industry presently has about double the productionfacilities necessary to meet production requirements.

Irrigation development is another example. New technologies (sophisticated sprinkler systems) have made it possible to irrigate marginal range land which is highly susceptible to erosion. A high-income developer and investor can recover about one-third of the purchase price of such land through federal and state tax breaks on the irrigation development, according to the Center for Rural Affairs. Ironically, the tax breaks work to encourage the selection first of those parcels which are most vulnerable to erosion (the higher the ratio of development costs to original purchase price of the land, the larger the tax breaks; the lover the purchase price, the more marginal the land). Most of the production from these developments is corn, a commodity already in surplus.

Theological Rationale

A Christian ethical approach to agriculture begins with the acknowledgment that “The earth is the Lord’s and the fulness thereof…” God the Creator has given human beings a special position in the world, with specific responsibility for the fruits of tie earth and all living things. Thus the production of food and fiber — the primary task of farmers — becomes a service to God and humankind.

The Christian faith also attaches special significance to the family, where Christian love and forgiveness can be personally experienced. The family farm has provided, throughout our history, that type of rural environment most co to the growth of human personality, the stability and enrichment of family life, and the strength of the community and its institutions. This pattern of agriculture he also contributed notably to national strength and the preservation of democratic attitudes and practices.

Therefore, the preservation and extension of the efficient family-type farm as the predominant pattern of American agriculture has been affirmed as a conscious goal of national policy by the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Furthermore, the Christian concept of justice demands that family farmers who produce efficiently and abundantly, where such production is in the national interest, should not suffer from this fact, but should receive economic rewards comparable with those received by persons operating larger-than-family-type farms or by persons of similar competence in other vocations.

Because of their ineffective bargaining position, farmers have rarely enjoyed true parity of income in the open market except during wartime periods of extreme demand. Yet sustained farm income is essential both as a requirement of justice for farmers – and of stability for the total economy. Therefore, programs designed in accordance with sound economic principles and equitably administered to protect the rights and interests of small as well as large farmers are a legitimate and necessary function of the federal government.

————————————————————————————————–

1. A commonly accepted definition of the “family farm” is a farm operation in which the responsibility of ownership, management, financial risk and labor (except at peak seasons) is that of the family.

2. The economic literature on economies of scale and farm size are voluminous and conclusive. A farm which fully employs one or two persons achieves lowest costs and optimum efficiencies. The classics in this literature are: J. Patrick Madden, Economies of Size in Farming, AER Report #107, USDA, 1967, Warren R. Bailey, The One-Man Farm, ERS-519, USDA, 1973; and Thomas A. Miller, et al, Economies of Size in U.S. Field Crop Farming, AER Report #472, USDA, 1981. The entire issue was reexamined by USDA as part of the “structure of agriculture” project conducted by the agency in 1980. It confirmed previous findings that “most of the technical economies…are attained at relatively small sizes” and concluded that “we have passed the point where any net gain to society can be claimed from policies that encourage large farms to become larger”. (A Time to Choose, USDA, January 1981.)

3. Two of the Studies: A Time to Choose, January 1981, USDA Ch. 6, “Tax Policy” pg. 90-99. The Effects of Tax Policy on American Agriculture, Charles Davenport, Michael D. Boehlje, David B.H. Martin, USDA/ERS, Agricultural Economic Report #480. February 1982.

4. “Ethical Goals for Agricultural Policy”, Statement adopted by the General Board of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., June 4, 1958.

RESOLUTION ON THE STATUS OF BLACK OWNED FARM LAND IN THE UNITED STATES

Adopted by the Governing Board of the National Council of the Churches of Christ, November 11, 1983

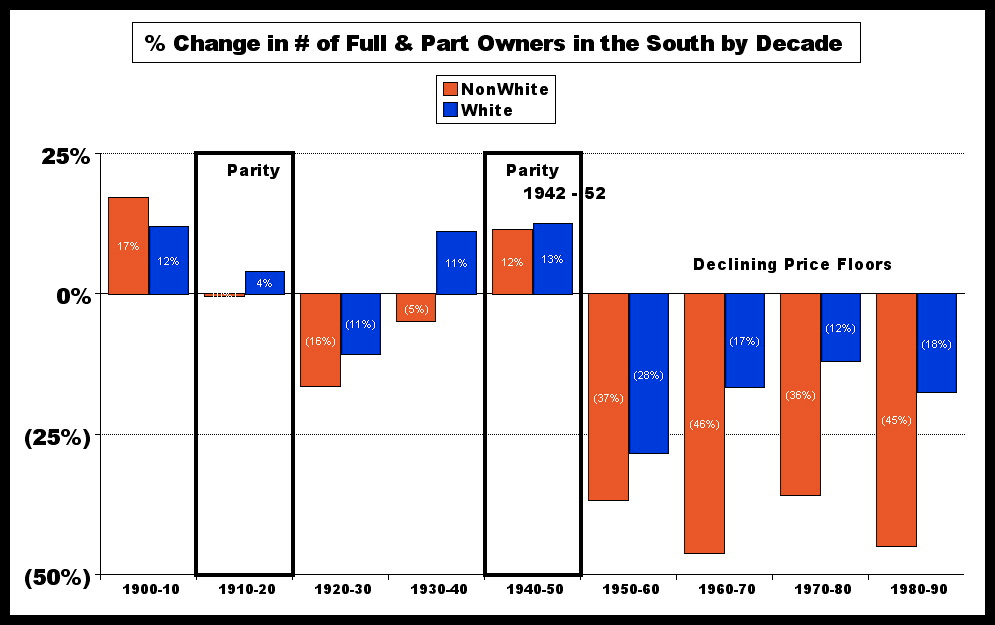

According to the Census in 1978, the rate of Black farmland loss was two and a half times greater than the loss rate for white farmers. Black farmers as a group, compared to other farmers, depend more heavily on farming for an income and have less off-farm income. The continuing loss of ownership and control of agricultural land by Black American farmers has reduced their ability to achieve economic viability and financial independence. This loss has been accelerated by the Black land owner’s lack of access to capital, technical information and legal resources needed to retain and develop agricultural land holdings into stable, income-producing self-sustaining operations.

Resolved: that the Governing Board of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. calls upon the Congress, the Administration and in particular the United States Department of Agriculture to develop and implement a Federal program designed;

1) to prevent the loss of ownership of agricultural land by Black Americans;

2) to assist Black Americans to acquire such land or to expand present holdings; and

3) to achieve a significant increase in the participation of Black American owners of agricultural land in applicable Federally sponsored programs.

This program should:

1) identify, reduce and eliminate barriers which have resulted in reduced participation by Black farmers in, and reduced benefits from, Federally sponsored programs.

2) provide technical assistance to Black Americans who seek to develop or upgrade land for agricultural purposes,

3) identify Black Americans who may wish to acquire land for agricultural purposes and to target applicable existing Federal programs to assist in such acquisition, and

4) encourage the development of private-sector initiatives directed toward the achievement of these objectives.

The Governing Board,concerned about the increasing disappearance of American small farms, especially those owned and operated by American Blacks, urgently calls upon its-member denominations, local congregations and affiliate organizations to advocate and support these measures.

Policy Base: Ethical Goals for Agricultural Policy June 4, 1958

BACKGROUND STATEMENT REGARDING PROPOSED RESOLUTION ON BLACK OWNER FARM LAND

Psalm 24: The earth is the Lord’s and all that is in it, a the world and those who dwell therein.

Isaiah 58:6 Is not this what I require of you…to loose the fetters of injustice….

A Christian ethical approach to agriculture begins with the acknowledgment that “The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof…” God the Creator has given human beings a special position in the world, with specific responsibility for the fruits of the earth and all living things. Thus the production of food and fiber — the primary task of farmers — becomes a service to God and humankind.

Land development promotes community stabilization, creates opportunities for profitable investments and benefits local and national economies by strengthening the economic independence of farmers and creating profitable markets for goods and services.

During a ten-year period ending in 1978, Blacks lost 57 percent of their active farmland base — down from 133,000 operating farms comprised of 6.2 million acres in 1969 to 57,000 farms and 4.2 million acres in 1978. The two million acre loss over 10 years is conservatively valued at 1 billion dollars.

Farmland is included in the Census of Agriculture count every five years if it produces an income for its owner of at least $1,000 a year. The Census has an information base on only those Blacks who derive at least $1,000 in farm sales a year. They numbered 57,000 controlling 4.2 million acres in 1978.

The Emergency Land Fund, Atlanta,- Georgia, und r contract to the Farmer‘s Home Administration. U.S. Department of Agriculture, made a study of “The Impact of Heir Property on Black Rural Land Tenure in the Southeastern Region of the United States” in 1980 and developed the following data:

“In 1974, Blacks owned or had access to 9.5 million acres with as many as 1.6 million individual Black owners who were scattered throughout the United States with a land title in the rural Southeast. Therefore, over two-thirds of the Black farmland base, some 5 million acres, receive no policy attention, and most certainly none of the program resources available through public supported agricultural institutions. This category of “unaccounted for” Black rural land

is often idle, subject to absentee ownership, occupied by elderly individuals who are often on public assistance, who in many cases cannot read or write well, if at all, encumbered with clouded titles, lost in tax, partition and foreclosure sales and an easy prey for land speculators. According to the Census in 1978, the rate of Black farmland loss was two and a half times greater than the loss rate for white farmers.

“Black farmers as a group, compared to other farmers, depend more heavily on farming for an income and have less off-farm income. Additionally, the net farm and farm-related income earned per dollar value of land and building represents a 15% return on investment by the Black farmer compared to the 9% average for all farms. Blacks, therefore, are good farmers but continue to lose land because of a lack of farm financing and operating capital, and suffer also because of the lack of land utilization information. technical and management assistance and markets. There is also a host of legal. financial and discrimination problems that are contributing factors. Often these problems involve both public and private lending institutions, courts, legal representation and land speculators – both private and corporate.”

Secretary Block of the U. S. Department of Agriculture appointed a special Task Force on the “Decline of Blacks in Agriculture” in April 1983. The information in this resolution will support the Emergency Land Fund’s recommendations to that Task Force.

Based on NCCC Policy Statement: Ethical Goals for Agricultural Policy, June 4, 1958.

———————————————————————————————

l. The Emergency Land Fund was founded-in 1971 by Robert S. Browne, who is also the founder of the Black Economic Research Center and the Twenty-First Century Foundation. For the past eleven years, ELF has maintained a regional focus, working throughout the rural Southeast providing a variety of services and conducting special projects and programs aimed at the retention, acquisition and better utilization of farmland for the benefit of Blacks. ELF’s services include legal, financial, technical and management assistance. Additionally, ELF has maintained an extensive outreach and community education program. Emergency Land Fund, Joseph Brooks, President, 564 Lee Street, S.W., Atlanta, Georgia 30310 (404) 758-5506

A RESOLUTION

of the

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF THE CHURCHES OF CHRIST IN THE U.S.A, 475 Riverside Drive, New York, NY 10115

Resolution on the Exploitation of the Rural Crisis by Extremist Organizations

(Adopted by the Governing Board November 8, 1985)

The Governing Board of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A.:

Endorses as its own statement the resolution adopted on April 13, 1985, by the Iowa Inter-Church Agency for Peace and Justice, an agency of the Iowa Inter-Church Forum, and member of the Iowa Farm Unity Coalition:

“We deplore and reject the extremist philosophies and actions of those individuals and organizations that promote violence, anti-semitic, or racist responses to the Farm Crisis, and reaffirm and recommit our efforts and energies to building a constructive, progressive, non-violent farm movement that is committed to justice for all people of this nation and the world.”

(2) Urges the member communions to communicate this Resolution to their congregations along with materials which will inform them about this racist and anti-semitic campaign, and how to combat it.

Policy Bases: “Religious and Civil Liberties in the United States of America,” adopted by the General Board October 5, 1955. “Ethical Goals for Agricultural Policy,” adopted by the General Board June 4, 1958.

A RESOLUTION of the NATIONAL COUNCIL OF THE CHURCHES OF CHRIST IN THE U.S.A.

475 Riverside Drive New York, NY 10115

Resolution on the Save-the-Family-Farm Act of 1986

(adopted by the Governing Board, November 6, 1986)

The Governing Board of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. endorses

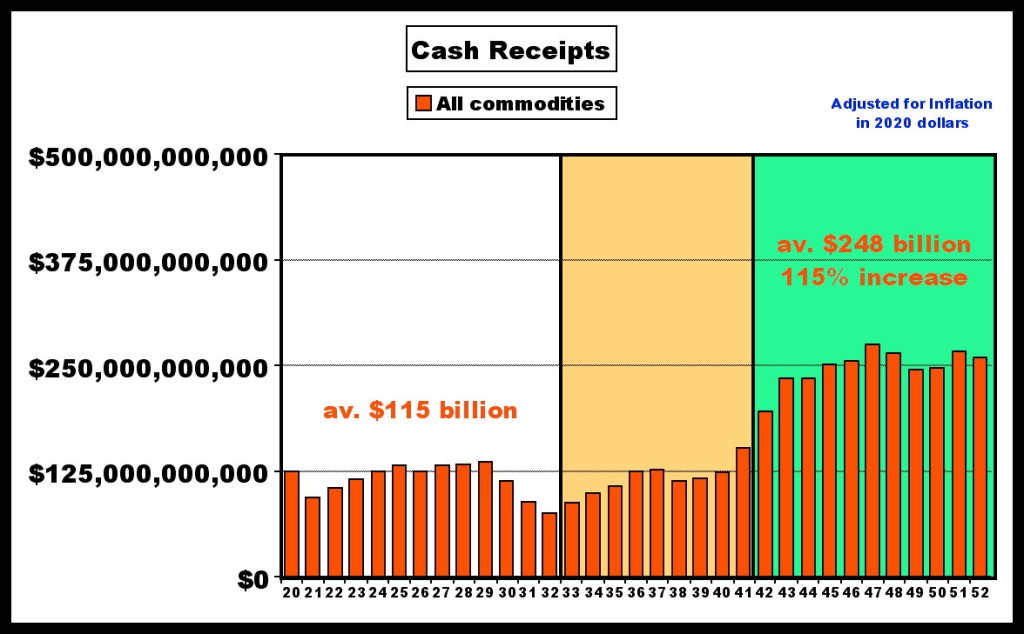

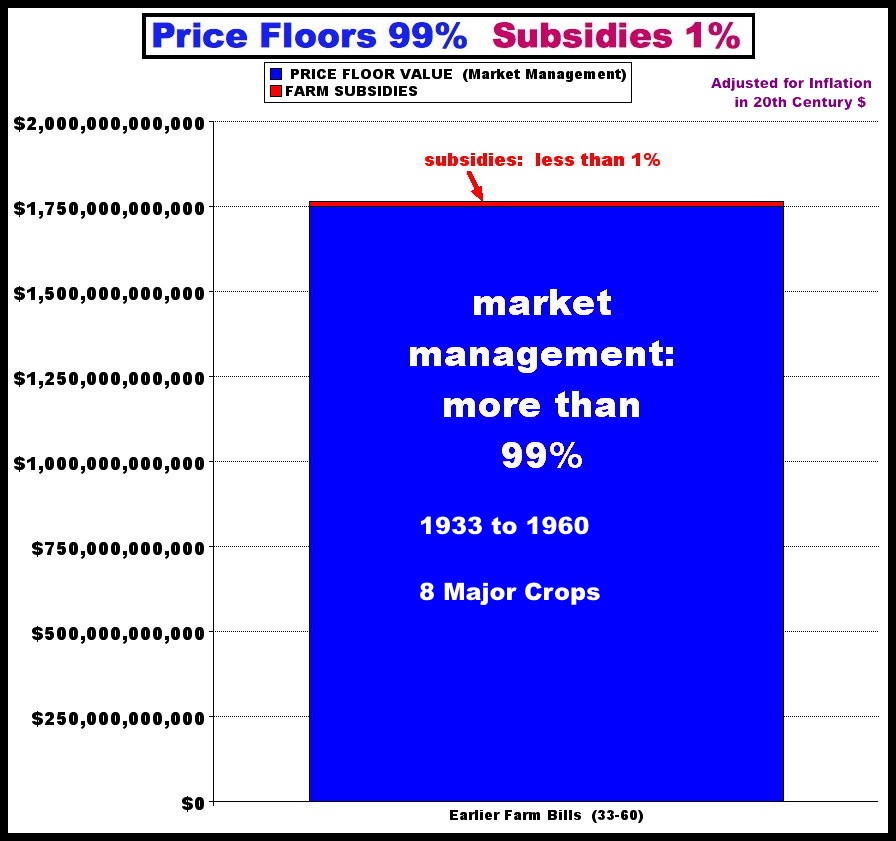

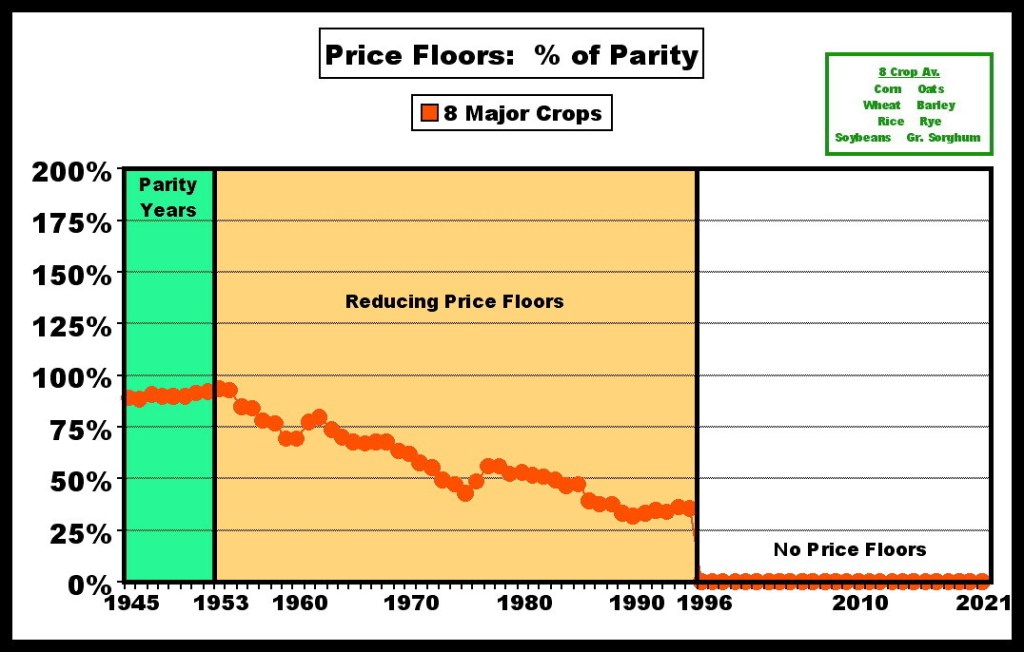

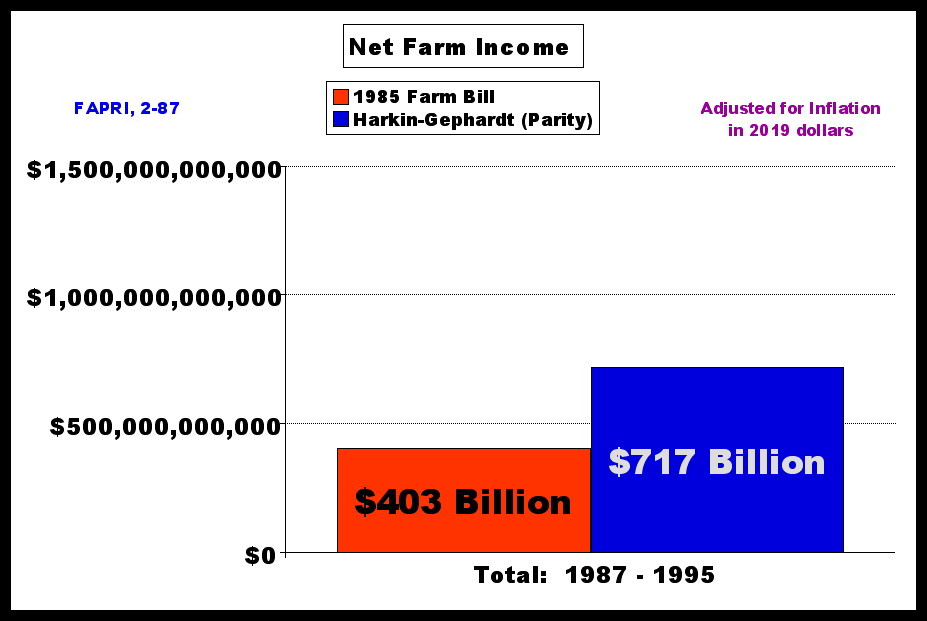

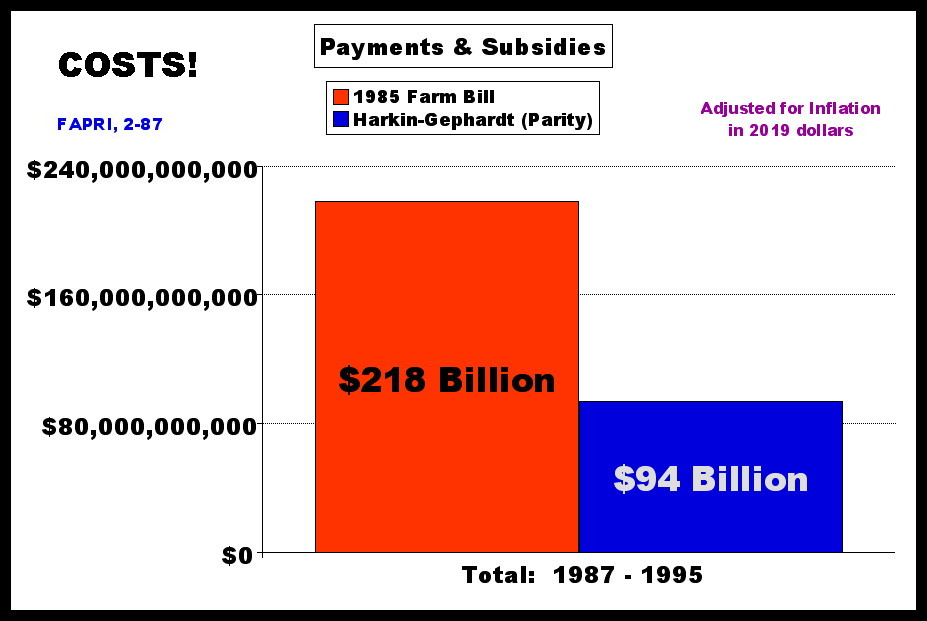

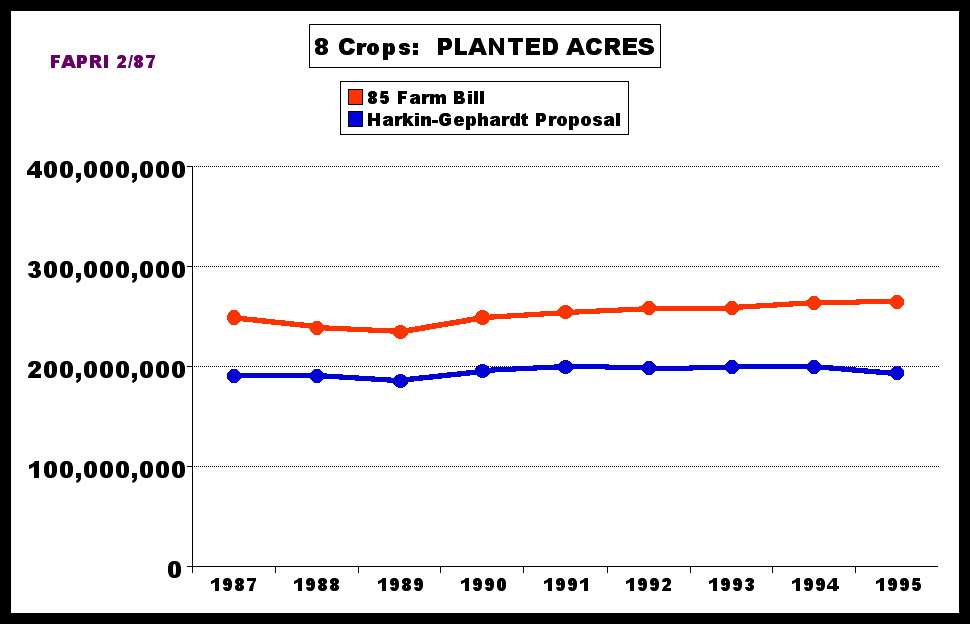

(1) The objectives of the Save-the-Family-Farm Act of 1986, which incorporates a strong supply-management program; price supports that cover at least the cost of production; a producer referendum that will enable farmers and ranchers to determine their own future; and a minimization of the financial burden of federal farm programs on the taxpayer.

The Governing Board of the National Council of Churches instructs

(1) The General Secretary to ask Congress and the appropriate Committees of Congress to docket this proposed legislation for immediate consideration upon the convening of Congress in January 1987.

(2) The General Secretary is also instructed to inform the President of the United States and the Secretary of Agri- culture of this action by the National Council of Churches and our expectation for support from the administration.

Policy Base: Ethical Goals for Agricultural Policy, June 4, 1958.

For presentation to Document_________

NCC Governing Board

November 5-7, 1986

Resolution on the Save-the-Family—Farm Act of 1986

Since 1984 the Rural Crisis Issue Team, an ecumenical group of staff persons, responding to a directive from toe Governing Board of the National Council of Churches, has been advocating change in the legislation governing the farm economy. The directive from the Message, “Rural Crisis: A Call for Justice and Action”, states the following:

“to press for enlightened public policy that will preserve the diverse ownership of land and the continuation of the family farm system with its attendant values of stewardship, family, and community responsibility through education and organized action within the congregations of our member Communions.”

The Governing Board has put the National Council on record in Resolutions to support the status of the family farm as it relates to farm tax and credit policies, loss of Black-owned farm land, to warn against extremist organizing in the rural communities, and to respond to the economic development needs from the drought crisis on the farms in the southeastern states.

The Federal Office of Technology Assessment, Spring 1986, stated that “if present trends continue to the end of this century, the total number of farms will continue to decline from 2.2 million in 1982 to 1.2 million in 2000“.

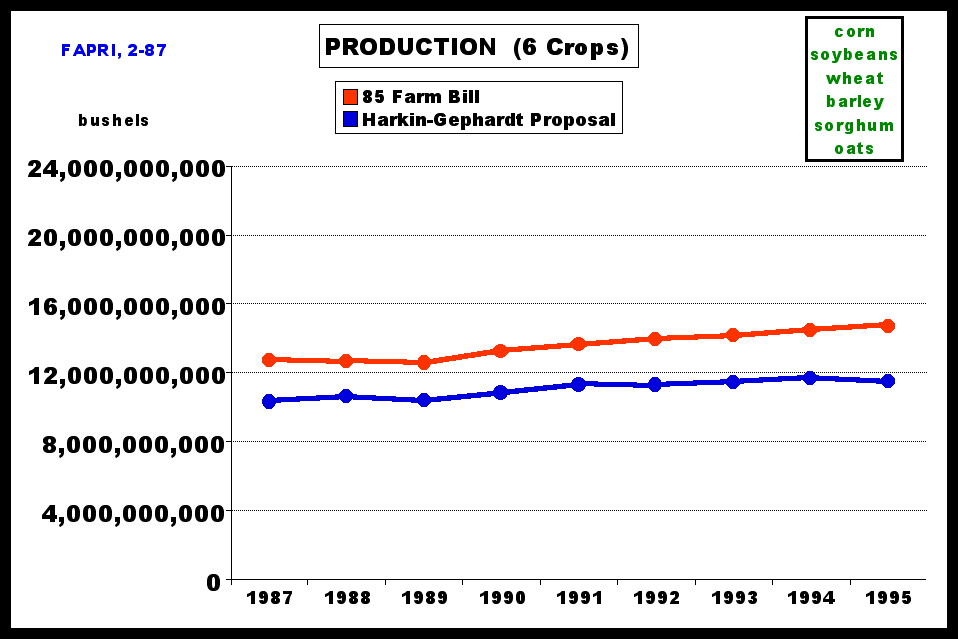

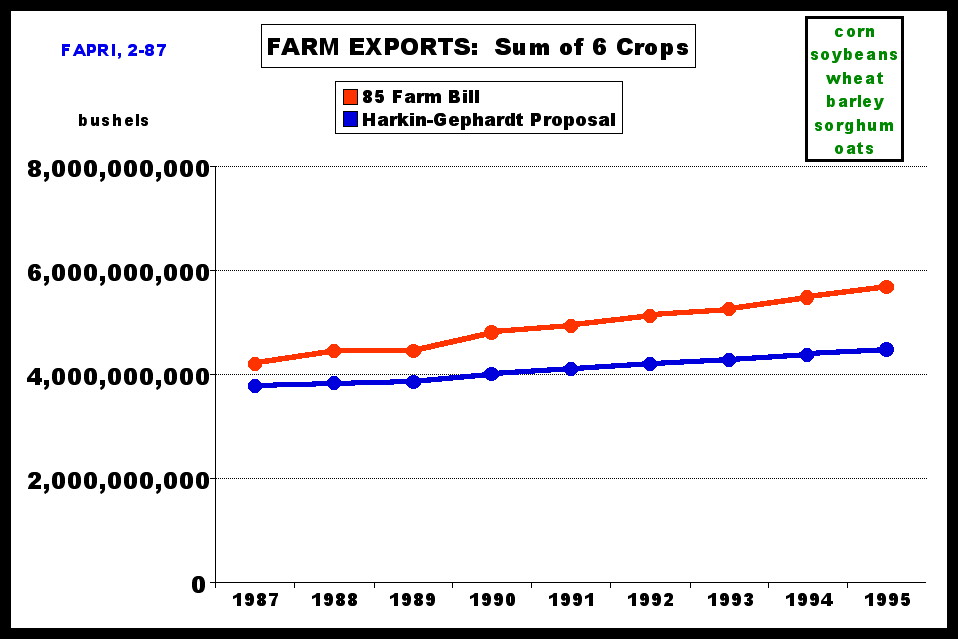

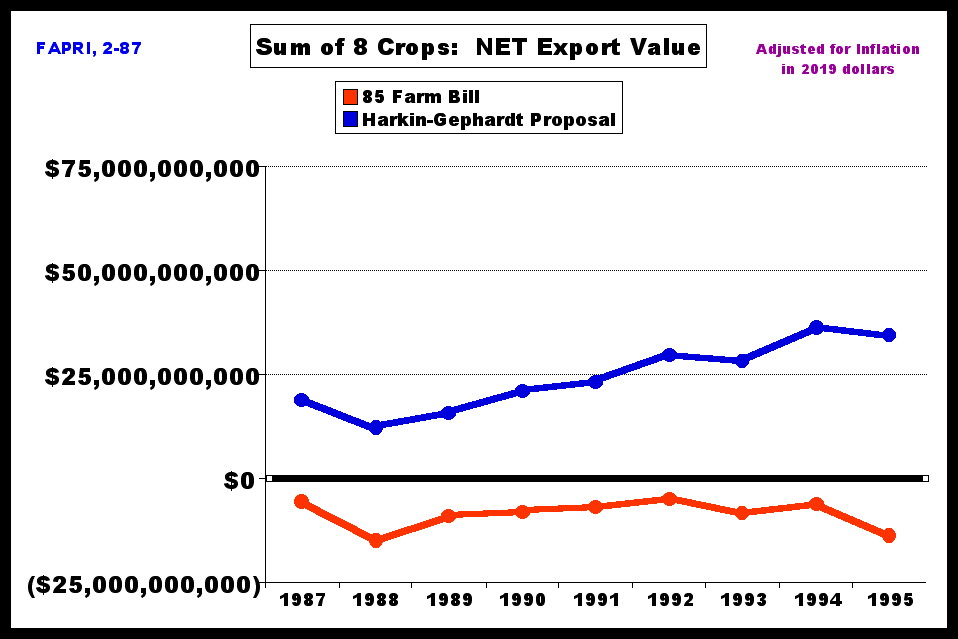

Legislation to reopen the debate on the problems facing family farmers was introduced into the Senate and the House of Representatives on September 23, 1986. The Save-the-Family-Farm Act of 1986 challenges the Food Security Act of 1985, the most recent legislation on farm policy. The new legislation is supported by a broad-based coalition of farmers, consumers, laborers, church leaders, small businesses, bankers and community leaders. The Save-the-Family-Farm Act seeks to control overproduction of farm products while restoring supply/demand balance to the marketplace. It is designed to save dollars for the taxpayer and save America’s family farms and rural communities.

The Governing Board of the National Council of Churches endorses the objectives of the Save-the-Family Farm Act of 1986, which incorporates a strong supply-management program; price supports that cover at least the cost of production; a producer referendum that will enable farmers and ranchers to determine their own future; and a minimization of the financial burden of federal farm programs on the taxpayer.

The Governing Board of the National Council of Churches instructs the General Secretary to ask Congress and the appropriate Committees of Congress to docket this proposed legislation for immediate consideration upon the convening of Congress in January 1987.

The General Secretary is also instructed to inform the President of the United States and the Secretary of Agriculture of this action by the National Council of Churches and our expectation for support from the Administration.

Note accompanying analysis of Save-The-Family-Farm, Act of 1986.

RESOLUTION ON THE “CHRISTIAN IDENTITY” MOVEMENT

Since its beginnings, the National Council of Churches has voiced opposition to all forms of racism and anti-semitism. It has expressed concern about the recurring signs of Nazism and for the victims of Klu Klux Klan violence. In the Theological Statement of Racial Justice, the Governing Board reiterated this concern when it stated that:

“Racism is an expression of idolatry replacing faith in the God who made all people and who raised Jesus from the dead with the belief in the superiority of one race over another or in the universality of a particular form of culture.”

Because of the “Christian Identity” movement’s ideological under- girding for racist violence, it represents a threat to the Christian understanding of the Gospel. “Identity” doctrine is preached at rallies by the para-military White Patriot Party in North Carolina, at survivalist encampments in many sections of the Midwest, and in the halls of the Aryan Nation in the Pacific Northwest. “Christian Identity” played a major role in The Order, an armed criminal underground organization. In addition, Identity ideology has promoted a practical working unity among geographically disparate organizations and groups.

“Christian Identity” centers around the belief that the people of Northern Europe — white Anglo-Saxons — are the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Jews are considered to be the Children of Satan, and racial ethnic people are considered to be “pre-Adamic” — a lower species than people of European ancestry.

“Christian Identity” is neither a single organization nor a monolithic doctrine. Instead it is composed of hundreds of small groupings throughout the United States. It is not confined to any single region of the country, and small Identity churches exist in metropolitan areas like Los Angeles and in the rural hills of Arkansas. Some Identity groups are directly engaged in political action — often violent political action and others are content simply to pass their racist heritage on to their children. Therefore, the most helpful model with which to understand “Christian Identity” is to regard it as a movement rather than a denomination. The Identity movement is composed of interactive parts that continually develop and re-develop its ideological and organizational expression.

The development of para-military activity within the Identity movement is tue result of a convergence of the impulse towards armed violence within the general racist population and an impulse towards armed activity from within Identity ideology itself. Any analysis of para-military activity within the Identity movement must take both sources into account. “Christian Identity” has emerged as a primary religious and spiritual orientation of the Far Right. It incorporates the major neo-Nazi themes, while maintaining itself as an “American” phenomenon. Recently the U.S. has been undergoing a resurgence of bigotry under the guide of Christianity. This resurgence is a deep, ugly stain in American society.

THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED that the Governing Board of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the USA:

Reaffirms its commitment to Racial Justice and its opposition to the ideology of the “Christian Identity” movement.

2. Condemn the Identity movement’s perversion of Christianity as a pretext for hatred, racism and anti-semitism.

3. Calls on its member communions to educate their constituencies about the nature and purpose of the “Christian Identity” movement.

4. Calls on the Division of Church and Society to keep the NCCC member communions informed about the “Christian Identity” movement.